FILE SYSTEM AND OS OPERATIONS

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- Introduction to File System Operations

- Understanding File Paths

- File Operations in Python

- Directory Operations

- Working with Paths using os.path

- pathlib — The Modern Approach

- Advanced File Metadata (stat)

- File Permissions and Access Control

- Copying, Moving, and Archiving Files (shutil)

- Recursive Directory Traversal

- File Pattern Matching (glob)

- Temporary Files and Directories

- Environment Variables

- System Commands and Shell Interaction

- Process Management

- Error Handling and Exceptions

- Performance Best Practices

- Security Best Practices

- Real-World Application Examples

- Complete Summary

Modern software interacts with the file system constantly. Whether an application reads configuration files, writes logs, organizes datasets, processes images, manipulates directories, runs scheduled backups, or performs system-level automation, file system operations are unavoidable. Python, being a high-level and expressive programming language, offers some of the simplest yet most powerful ways to interact with files, directories, and the operating system.

This comprehensive chapter serves as a deep exploration of Python’s file system and OS operations, covering not only the core built-in libraries like os, os.path, pathlib, shutil, glob, and stat, but also the concepts behind them. It includes theory, practical code examples, best practices, common pitfalls, performance considerations, and real-world use-cases.

By the end of this chapter, you will understand how Python interacts with the underlying operating system, how files and processes work, how to manipulate data safely, and how to build reliable file-based applications.

1. INTRODUCTION TO FILE SYSTEM OPERATIONS

A file system is the structure used by the operating system to store and organize files. Every OS—Windows, macOS, Linux—has a slightly different file system behavior, yet Python provides a cross-platform interface to interact with all of them seamlessly.

Why File System Operations Matter

- Reading configurations, logs, and user data.

- Handling uploads and downloads.

- Automating cleaning tasks or backups.

- Processing datasets in data analysis and machine learning.

- Managing large directory structures in enterprise systems.

- Creating installers or deployment scripts.

- Packaging resources for applications.

Python offers two primary philosophies for file system handling:

- os and os.path — procedural, legacy, close to system-level operations.

- pathlib — modern, object-oriented, cleaner, and generally recommended for new code.

Both coexist, and understanding both is essential for handling real-world codebases.

2. UNDERSTANDING FILE PATHS

2.1 Absolute vs Relative Paths

- Absolute path starts from the root (/ on Unix, C:\ on Windows).

- Relative path is computed from the current working directory.

Example:

/home/user/documents/file.txt (Linux absolute)

C:\Users\Admin\file.txt (Windows absolute)

documents/file.txt (Relative)

2.2 The Current Working Directory (CWD)

Python programs execute relative to the current working directory.

import os

print(os.getcwd()) # get current working directory

To change it:

os.chdir("/path/to/new/location")

Changing CWD is powerful but must be used carefully because it affects all follow-up file operations.

3. FILE OPERATIONS IN PYTHON

The core of file interaction is built into Python's standard library via the open() function.

3.1 Opening Files

f = open("data.txt", "r")

content = f.read()

f.close()

Modes:

- "r" – read

- "w" – write (overwrites file)

- "a" – append

- "x" – exclusive creation

- "rb", "wb" – binary modes

3.2 The With-Statement (Context Manager)

The recommended way to handle files:

with open("example.txt", "r") as f:

data = f.read()

Advantages:

- Automatically closes the file

- Prevents resource leakage

- Handles exceptions gracefully

3.3 Reading Files

content = f.read()

line = f.readline()

lines = f.readlines()

3.4 Writing Files

with open("out.txt", "w") as f:

f.write("Hello")

f.writelines(["A\n", "B\n"])

3.5 Working with Binary Files

Common for:

- Images

- PDFs

- Audio

- Video

- Serialized objects

with open("photo.jpg", "rb") as f:

data = f.read()

3.6 File Position and Seeking

f.seek(0) # go to beginning

f.seek(10) # move to byte 10

pos = f.tell() # current position

3.7 Checking File Existence

import os

if os.path.exists("file.txt"):

print("File exists")

4. DIRECTORY OPERATIONS

4.1 Creating Directories

os.mkdir("new_folder")

os.makedirs("path/to/new/folder", exist_ok=True)

4.2 Removing Directories

os.rmdir("folder") # fails if not empty

shutil.rmtree("folder") # removes everything inside

4.3 Listing Directories

os.listdir(".")

Better: using os.scandir() for performance.

with os.scandir(".") as entries:

for entry in entries:

print(entry.name, entry.is_file(), entry.is_dir())

5. WORKING WITH PATHS USING OS.PATH

5.1 Joining Paths

path = os.path.join("folder", "file.txt")

5.2 Splitting Paths

os.path.split(path)

os.path.splitext(path)

5.3 Normalizing Paths

os.path.normpath()

os.path.abspath()

5.4 Finding Basename and Directory Name

os.path.basename()

os.path.dirname()

6. PATHLIB — THE MODERN APPROACH

pathlib is object-oriented and more readable.

from pathlib import Path

p = Path("folder/file.txt")

6.1 Joining Paths

new = p.parent / "newfile.txt"

6.2 Reading and Writing Files

content = p.read_text()

p.write_text("Hello World")

binary_data = p.read_bytes()

6.3 Creating and Removing Directories

Path("new_dir").mkdir(parents=True, exist_ok=True)

Path("new_dir").rmdir()

6.4 Traversing Directories

for f in Path(".").iterdir():

print(f)

For recursion:

Path(".").rglob("*.py")

7. ADVANCED FILE METADATA (STAT)

Metadata includes file size, timestamps, permissions, and owner information.

import os

info = os.stat("file.txt")

print(info.st_size)

print(info.st_mtime)

stat module provides constants for permissions:

import stat

mode = info.st_mode

print(stat.S_ISDIR(mode))

8. FILE PERMISSIONS AND ACCESS CONTROL

8.1 Changing Permissions (chmod)

os.chmod("script.sh", 0o755)

8.2 Checking Access

os.access("file.txt", os.R_OK)

os.access("script.sh", os.X_OK)

8.3 Owners and Groups (Unix)

info.st_uid

info.st_gid

9. COPYING, MOVING, ARCHIVING (SHUTIL)

shutil simplifies common file operations.

9.1 Copy Files

import shutil

shutil.copy("a.txt", "b.txt")

9.2 Copy with Metadata

import shutil

shutil.copy2("a.txt", "b.txt")

9.3 Moving Files

shutil.move("file.txt", "new_location/")

9.4 Deleting Trees

import shutil

shutil.rmtree("folder")

9.5 Creating Archives

import shutil

shutil.make_archive("backup", "zip", root_dir="data")

9.6 Extracting Archives

import shutil

shutil.unpack_archive("backup.zip", "out_folder")

10. RECURSIVE DIRECTORY TRAVERSAL

Most real-world tasks involve scanning nested folders.

10.1 Using os.walk

for root, dirs, files in os.walk("."):

print(root, dirs, files)

Useful for:

- Bulk processing

- Folder analysis

- Duplicate file detection

- Data pipelines

10.2 Example: Delete all .tmp files

for root, dirs, files in os.walk("."):

for f in files:

if f.endswith(".tmp"):

os.remove(os.path.join(root, f))

10.3 Example: Count total size

total = 0

for root, dirs, files in os.walk("."):

for f in files:

total += os.path.getsize(os.path.join(root, f))

print(total)

11. FILE PATTERN MATCHING (GLOB)

glob matches filenames using wildcards.

import glob

files = glob.glob("*.txt")

files = glob.glob("data/*.csv")

files = glob.glob("images/**/*.jpg", recursive=True)

Examples:

- Finding files by pattern

- Searching folders by type

- Bulk operations

12. TEMPORARY FILES (TEMPFILE MODULE)

Useful for:

- Caching

- Testing

- Secure temporary storage

import tempfile

with tempfile.TemporaryDirectory() as tmp:

print(tmp)

Temporary files auto-delete, preventing clutter.

13. ENVIRONMENT VARIABLES

What It Is:

Environment variables are key–value pairs maintained by the operating system that store configuration information outside a program’s code. They allow applications to access system-level settings such as paths, credentials, environment modes, and runtime configurations without hard-coding them.

In Python, environment variables are commonly accessed using the os module. They provide a secure and flexible way to control application behavior across different systems (development, testing, production).

Why They Are Used:

- Store sensitive data (API keys, passwords) securely

- Configure application behavior without changing code

- Maintain portability across operating systems

- Separate configuration from logic

Common Examples:

- PATH – System executable paths

- HOME / USERPROFILE – User directory

- PYTHONPATH – Python module search path

- Custom variables like DEBUG, ENV, DATABASE_URL

Typical Use-Cases:

- Managing application settings

- Controlling debug and production modes

- Accessing credentials securely

- System-level configuration management

Get environment variable

os.getenv("HOME")

Set environment variable

os.environ["DEBUG"] = "1"

Listing all variables

os.environ

14. SYSTEM COMMANDS USING OS AND SUBPROCESS

14.1 Execute simple commands

os.system("ls -l")

14.2 Better: subprocess

import subprocess

result = subprocess.run(["ls", "-l"], capture_output=True, text=True)

print(result.stdout)

Use subprocess for:

- Running other programs

- Automating shell tasks

- Running compilers, database tools, scripts

15. PROCESS MANAGEMENT (PID, FORK)

15.1 Get current PID

os.getpid()

15.2 Get parent PID

os.getppid()

15.3 Forking (Unix only)

pid = os.fork()

if pid == 0:

print("Child")

else:

print("Parent")

16. ERROR HANDLING AND EXCEPTIONS

Always handle file errors gracefully.

Common exceptions:

- FileNotFoundError

- PermissionError

- IsADirectoryError

- NotADirectoryError

- OSError

Example

try:

with open("file.txt") as f:

data = f.read()

except FileNotFoundError:

print("File not found")

except PermissionError:

print("Access denied")

Error handling is essential in production code.

17. PERFORMANCE BEST PRACTICES

17.1 Use with-statements

Prevents leaks and improves reliability.

17.2 Prefer pathlib

Cleaner and safer.

17.3 Avoid reading entire large files at once

Use chunked reading:

for chunk in iter(lambda: f.read(4096), ""):

process(chunk)

17.4 Use os.scandir instead of os.listdir for large directories

Scandir is much faster.

17.5 Avoid unnecessary disk writes

Cache data when possible.

18. SECURITY BEST PRACTICES

18.1 Validate filenames from user input

Avoid:

- Directory traversal attacks (../../etc/passwd)

- Unsafe temporary files

18.2 Use absolute paths for critical operations

Prevents CWD manipulation attacks.

18.3 Use Python's permission features correctly

Avoid world-writable files.

18.4 Never execute user-supplied shell commands

Use shlex.quote() if unavoidable.

19. REAL-WORLD APPLICATION EXAMPLES

19.1 Log File Analyzer

from pathlib import Path

def analyze(log_path):

errors = 0

for line in Path(log_path).read_text().splitlines():

if "ERROR" in line:

errors += 1

return errors

print(analyze("app.log"))

19.2 Bulk Image Organizer

from pathlib import Path

import shutil

for img in Path("photos").rglob("*.jpg"):

year = img.stat().st_mtime

dest = Path("archive") / year

dest.mkdir(parents=True, exist_ok=True)

shutil.move(str(img), dest)

19.3 Automatic Backup System

import shutil

from datetime import datetime

src = "project_data"

timestamp = datetime.now().strftime("%Y%m%d_%H%M%S")

backup = f"backup_{timestamp}"

shutil.make_archive(backup, "zip", src)

19.4 File Watcher (Polling-Based)

import time

from pathlib import Path

seen = set()

while True:

files = set(Path("watched").iterdir())

new = files - seen

if new:

print("New files detected:", new)

seen = files

time.sleep(1)

20. COMPLETE SUMMARY

This chapter demonstrated how Python offers a rich set of tools for interacting with files, directories, paths, system utilities, and OS-level operations. These capabilities enable Python programs to:

- Create, read, write, and update files

- Manage binary and text data

- Traverse directories recursively

- Manipulate paths robustly using pathlib

- Control file permissions and metadata

- Move, copy, compress, and delete files safely

- Access environment variables and execute system commands

- Handle errors gracefully

- Build real-world automation workflows

- Maintain performance and security best practices

Mastering file system and OS operations in Python transforms you from a script writer into a full-fledged automation engineer capable of handling real infrastructure, data pipelines, system-level integrations, and enterprise applications.

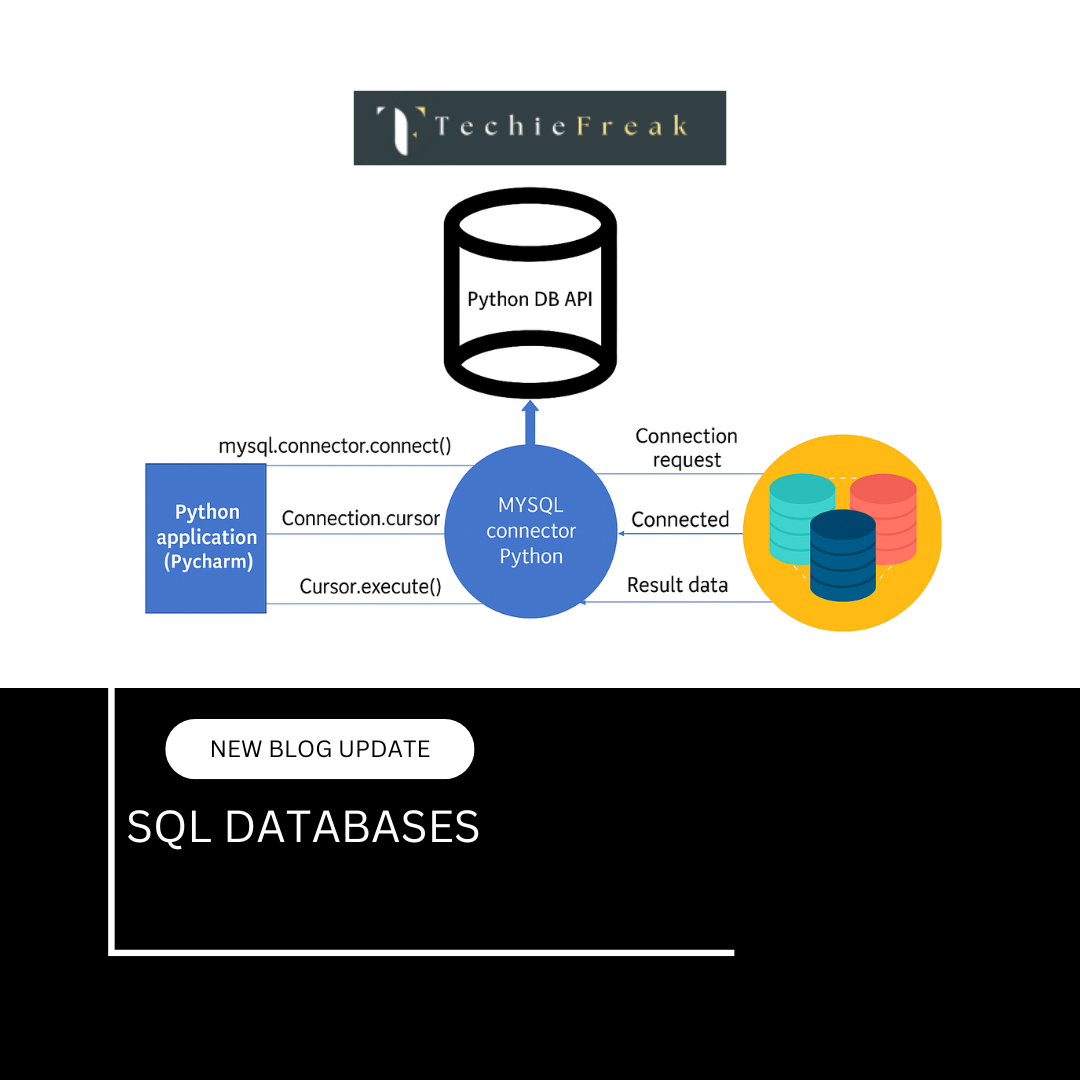

Next Blog- Python and Databases

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)